Exclusive extract: I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn

On Thursday 5th March 2015 we celebrated Sandy Denny as part of our Art School Counterculture event at Kingston Museum, exploring all the creative disciplines that art school students participated in, including music, poetry, theatre and dance. Thanks to all those who made the evening a success, including students from creative courses at Kingston, and all our performers. The images below capture the atmosphere of the evening:

Laura Ward, one half of Hickory Signals

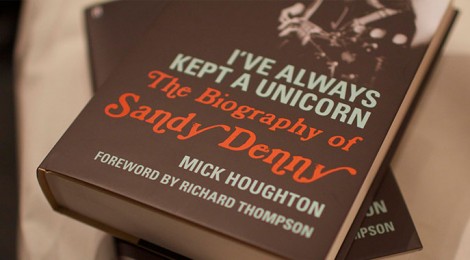

We were delighted that the Countculture event was also the Kingston launch for Mick Houghton’s new book I’ve Always Kept a Unicorn: The Biography of Sandy Denny (Faber & Faber).

In this exclusive extract adapted by Mick Houghton from his excellent new biography, we learn more about Sandy Denny’s connections to the art school and Kingston:

Born and brought up in Wimbledon, Sandy Denny attended Coombe Girls School after passing her 11+ and came away with five O-levels at the end of her fifth year. She stayed on to take art and music A-levels but dropped music because she had a run-in with her teacher. Then in February 1965, Sandy won a scholarship to Kingston Art School. Once she received the letter of acceptance to undertake the Pre-Diploma course, she immediately abandoned school.

During the six months before taking up her place Sandy was a temporary nurse at the Brompton Chest Hospital near Earls Court. It’s fair to say that it was in those months that she took her first real steps towards becoming a professional singer. Sandy was a pretty headstrong 18 year old and friends would say she was already an unstoppable force once she made her mind up to do something. By the time she went to art school in September she almost certainly knew she would drop out after a year because music was always going to be the path she followed.

Although, misleadingly, Sandy Denny said in interviews that she had first got up and sung at the Kingston Folk Barge while she was art school, she had already been doing floor spots in clubs as early as 1963. She would go along to local folk clubs with her friend Winnie. In particular they would take the bus to visit the Kingston Barge, a folk club started in 1961 by various local musicians including Dave Waite, who had by then formed a group called the Countrymen, inspired by American folk groups such as the Weavers and the Kingston Trio. ‘It was a converted coal barge,’ says Waite. ‘The most you could get in was about eighty people and it was an awful fire trap. People would pack the place out and musicians came from all over. Paul Simon played there, Jackson C. Frank, and Sandy; it’s where John Martyn first played when he came down from Scotland.’

Dave Waite vividly remembers seeing Sandy at the Barge. ‘It was definitely in 1963 when I first met this dumpy blonde girl who looked like a secretary bird. She was dressed in a twinset and pearls, pencil skirt and court shoes, and she looked a little out of place on our coal barge, and she asked if she could sing. When she got up and performed we were gobsmacked. We were absolutely stunned.

‘She had no skills in terms of presentation and she was shy and it was only with a little bit of urging that she did anything at all but she had such a sound – she had one of the most remarkable voices I’d ever heard. That was Sandy Denny and, as far as I know, it was the first time she had got up and done a floor spot.’

Sandy later recalled the incident herself: how she went along to the Barge and came away convinced she could sing better than anyone she saw. The next week, she plucked up courage and returned to the club. ‘The first time I ever stood up on stage my mouth went all dry,’ she said, ‘and I could hardly sing but when I came off and everybody applauded, I knew that although it was a great effort, I’d always want to do it.’ The nervousness before she went on was understandable but never entirely left her. She had got the bug.

Sandy could not have been better placed than growing up in Wimbledon to gain further experience in what was by then a flourishing folk scene. Whether it was folk or jazz or R & B groups now springing up, there were a lot of places to go in and around Wimbledon, Richmond, Twickenham, Putney and Kingston. The suburbs and towns along the Thames were as much at the heart of the folk, jazz and blues scene in the 1960s as Soho. If, as Sandy later described it, Soho had a folk club on every corner, then every other pub along the Thames seemed to have a regular folk club or folk night, and the same musicians played in both.

As a slight aside, in the early ’60s, Richmond and Twickenham were recognised centres of the growing British R&B scene, with The Crawdaddy Club and Eel Pie Island being two of the main venues. The Crawdaddy in Richmond was renowned because it was where the Rolling Stones had a residency and that was where Andrew Oldham first saw them play. When the Stones moved on the Yardbirds took over their slot. The Yardbirds also had a background at Kingston Art School. Even before one of its most famous students, Eric Clapton, joined the group, the original core members had originally come together as the Metropolitan Blues Quartet while at Kingston Art School.

The brilliant folk and blues guitarist John Renbourn, later a founding member of the group Pentangle, was another who went there. ‘I went to the art school at Kingston because I couldn’t do anything else and it was a bit of a catch-all for drop-outs. Some of the art-school types used to go to a pub in Hampton called the Feathers, and we’d sit around playing guitars and that’s where I first met Sandy. This was around 1964. We dossed about playing the blues and Sandy used to look in.

‘Even then, when she got up to sing she sounded great and stood out. She became the girlfriend of a singer who I used to play guitar with. He was always standing her up and we became friends. Then the next thing I knew she’d enrolled in the same art school, and I’m sure partly because so many of the musicians who were hanging round at the Feathers were from the art college.

‘It wasn’t that she didn’t want to do art, she was smitten by the whole music thing and she had aspirations even then. The rest of us were just sitting round getting drunk and stoned but Sandy already wanted to become a singer professionally. She was far more motivated than anybody I knew.’

Sandy finished her nursing stint on 24 August 1965, a month before taking up her place at Kingston Art School. By now she had made the transition from unpaid floor spots and open mic nights in local folk clubs to regular spots at the Troubadour which was within walking distance of the Brompton Hospital. She was simultaneously breaking into the pivotal network of pubs and clubs running off Shaftesbury Avenue and around Soho. Les Cousins or The Cousins on Greek Street was the best known and had opened in March 1965; Sandy played there as well as at the Scots Hoose on Cambridge Circus, Bunjies off Charing Cross Road, and Le Duce on D’Arblay Street.

John Renbourn remembers bumping into Sandy again after he was kicked out of Kingston Art School. He was getting by washing up in a Soho pub called the Coach and Horses. ‘She had followed the migration into that world and she took me to the Pollo restaurant on the corner of Old Compton Street and bought me a really big plate of spaghetti, which, at that time, meant a hell of a lot. She was so sweet-natured, had such a sunny disposition and a lovely laugh.’

The pull of the folk scene meant that Sandy wasn’t really socially involved in the school; she occasionally gave recitals there in the lecture room, but more often performed in more impromptu fashion, jumping up on the table in the canteen and singing unaccompanied. ‘It was throughout my year at college that [my career] just developed,’ Sandy later told the BBC World Service’s Clive Jordan. ‘I started doing gigs around the country and then it got to be a little bit too much, going to college and doing gigs and turning up late and having people congratulate me for coming in at two o’clock in the afternoon, so I decided that rather than waste everybody else’s time, I’d get out and do it.’

One of the first people Sandy met at Kingston was Gina Glaser, one of the resident artist’s models who was eight years older than her, and an accomplished singer. Glaser had arrived in London in 1958 with an intriguing history in the American folk revival of the fifties.

‘Gina was a fine, pure singer,’ recalls John Renbourn, ‘but she never pushed herself to do anything and never recorded commercially. She was really beautiful and she played guitar, banjo and dulcimer and knew people like banjo player Derroll Adams and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and her father was a folk organiser.’ Dave Van Ronk talks about her in his book The Mayor of MacDougal Street [which part inspired the film Inside LLewyn Davis]. She was part of the early folk movement before Dylan arrived in New York.

Glaser had come to London having heard there was work in the folk clubs for American singers. ‘I sang mostly in London, often at the Singers Club, but there were other less rigid folk clubs around Richmond, Putney and Kingston where I ended up living. Aside from maternity leave I was at Kingston Art School throughout the Sixties. I met Eric Clapton there in 1961, John Renbourn a couple of years later, and met Sandy when I went back there in 1965 after my daughter was born.’

In his self-titled autobiography, Eric Clapton says: ‘I met, and followed around for a while, an American female folk singer called Gina Glaser. She was the first American musician I had been anywhere near, and I was starstruck. Her speciality was old Civil War songs like “Pretty Peggyo” and “Marble Town”. She had a beautiful clear voice and played an immaculate clawhammer style.’ As his playing improved, Clapton began playing in a pub in Kingston called the Crown, until he was eventually thrown out of art college at the end of his first year.

‘Gina took Sandy under her wing and Sandy absorbed a lot from her,’ continues Renbourn. ‘She helped Sandy transform herself from being the girl in the pub singing Joan Baez songs to singing beautiful old songs and phrasing more like Gina.’

‘We talked about phrasing and technique,’ says Glaser, ‘which to me is the most important thing about singing. She used to tell people that I influenced her but I think it was more that I encouraged her, especially fostering her interest in traditional songs because that’s what I used to sing. Sandy knew she was good. She was insecure on many different levels but never about her music, at least not then.

‘I was not surprised when Sandy gave up art and left Kingston. They all gave it up – John Renbourn didn’t stay the whole course, Eric Clapton certainly didn’t. There were plenty who stuck around, got their degrees and who would end up teaching, but that’s not what Sandy wanted at all. It was a stepping stone to growing up. She enjoyed her time at Kingston. She was good too, her drawings were lovely. Kingston was a very competitive school and she would never have got in without definite skills. She liked sculpture but her thrust was always music; art soon became secondary to her.’

For Sandy the art school experience in the mid-Sixties was typical of so many musicians because it gave them the freedom to juggle playing music with classes and it brought them into contact with kindred spirits. As it was she joined the massed ranks art school drop outs which included Keith Richards who went to Sidcup Art School, Jimmy Page to Sutton, Pete Townshend went to Ealing, Ray Davies to Hornsey while Brian Ferry studied under Richard Hamilton in Newcastle; for all of them and not least Sandy Denny, art school was almost the classic training ground for future British rock stars – and folk rock stars – of the Sixties.

Photographs: Ezzidin Alwan / Digital Media Kingston University